Karie Atherton recalls the memorable summer she worked on a Wisconsin dairy farm. Flash forward many years later, and she’s running her own, Aires Hill Farm. While the hours remain long and the work hard, she continues to appreciate dairying.

“You’re never going to master it – there’s always a challenge,” she explains. “I guess that’s what appeals to me,”

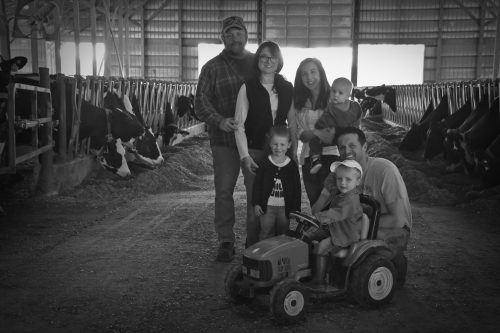

The farm in Berkshire, VT, is home to a herd of 400 Holsteins. Atherton is the primary manager and part-owner, responsible for all the decision-making in the daily operation of the farm. She took over in 2014 when her father, Edward Orlyn Thompson, and uncle, James Bryan (Bernie) Thompson, decided to retire.

Atherton attended Vermont Technical College with the goal of buying into the family operation, but the timing wasn’t right after she graduated. That led her to Wisconsin for that memorable summer, but she soon returned and worked with her father and uncle.

She currently milks 195 cows twice a day and has enjoyed a winning streak in terms of milk quality. The farm has been with St. Albans Cooperative Creamery since 1986, consistently earning awards for its high-quality milk, and in 2016, Atherton received an award from the co-op for Platinum Quality milk and for having two perfect inspection scores of 100.

Atherton isn’t content with only perfect scores, however – she recently received a matching $40,000 grant from the Vermont Housing and Conservation Board to purchase rumination collars to help monitor the cows’ activity, which alert the farmer to cows in heat or requiring attention. The grant also covers installation of a cow identification system in the milking parlor. “It’s like having a really good herdsman around,” she laughs.

Helping out at the farm is a reliable crew that includes Atherton’s soon-to-be four-year-old daughter, Maggie, “a dairy farmer in the making.” Atherton’s husband, Nick, works off the farm but spends his vacation pitching in as well.

Family is an important component to this operation. As Atherton points out, she’s seventh generation, with the first ancestor milking a cow back in 1823. “I’m a diehard,” she admits. “I don’t want to see it end.”

With the future in mind, Atherton is active in the St. Albans Co-op Young Cooperators, and also works with the Cold Hollow Career Center in Enosburg Falls, offering students an opportunity to work on the farm to learn about dairying.